Organizational leaders can no longer choose whether or not to have an ethical culture, with measurable and enforceable standards. The Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX) and the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for Organizations (FSGO) both dictate that leaders of organizations will be held liable for the oversight of their organization. New federal regulations remove the defense of ignorance, holding board of directors, CEOs, CFOs, and other leaders accountable for what employees do. This article looks at the process of developing ethical standards with regard to content, training and communication, and enforcement.

Organization Synergist (OS)

Developing Ethical Standards

The standards themselves are the nuts and bolts of the ethical culture being created and established. They come in the form of a code of conduct, a code of ethics, or a statement of values. The code of ethics is typically the most comprehensive, although all three forms are interchangeable. Participants in composing standards should be the president, board of directors, and the CEO (Ferrell et al., 2013). Two critical components most important when developing ethical standards are what Kranacher (2006) calls the tone at the top. Kranacher (2006) describes the tone at the top concept as, “a comprehensive program that goes beyond ‘setting a good example’ and ‘doing the right thing’; it requires an organization’s management to act on the principles embodied in its formal ethics policy” (Kranacher, 2006, p.80). No matter how well written the standards are or what format they take, they must be visibly supported and upheld by the actions of those at the top.

The second critical component of the standards is the content. They must reflect the desires of top management for compliance to the organization’s cultural values, rules, and policies. They should also address what Ferrell et al. describes as “high-risk activities that fall within the scope of daily operations” (Ferrell et al., 2013, p.223). Other considerations for inclusion are:

1). Stating risk areas complemented with the values and the explicit conduct that is necessary for compliance with laws and regulations. In other words, do not assume that readers are capable of connecting the values and knowing the right conduct. When you spell out the values and conduct, it makes it easier for them to obey (Ferrell et al., 2013).

2) Identifying and addressing the specific ethical issues that are relevant to the organization. This, of course, is indicative of the fact that an analysis must precede the construction of the ethics program (Ferrell et al., 2013).

3) Consider values from the stakeholders’ perspective, and look for areas of overlap, where stakeholders and organization values are the same. Including stakeholder values creates inclusiveness and unity among the organization and its stakeholders (Ferrell et al., 2013).

4) Use examples to reflect values. Draw pictures for people to help them understand the value behind the rule or procedure. When people understand why they are being asked to do something, they become more agreeable (Ferrell et al., 2013).

5) The code must be communicated frequently and in a way that people can thoroughly understand (Ferrell et al., 2013).

6) The code should be revised each year, allowing input from all stakeholders. As the organization grows, new issues will arise and need to be included. This is a continuing project (Ferrell et al., 2013).

Training and Communicating the Ethics Program

A major component to establishing an ethical culture is ethics training. According to Ferrell et al., three factors influence ethical decision-making of employees: the corporate culture, co-workers and supervisors, and opportunities to engage in unethical behaviors. Ethics training can impact all three areas of influence. Employees who understand their company’s philosophical position on ethical behavior are less likely to engage in unethical behaviors. Every department manager must be involved in the development of ethics training, which should be individualized for the unique features of the organization. Components of an effective training program should include: a theoretical foundation, a code of ethics, procedural guidelines for airing ethical issues, involvement from both line and staff, and explicit executive priorities regarding ethics (Ferrell et al., 2013).

When creating and establishing a new ethical culture in an organization, training can be used as a strategy for building shared vision. It is through genuinely shared vision that leaders are able to obtain commitment and focus from their members. Peter Senge (1994) in his book, “The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook,” shares the story of Vaclav Havel, who was elected president of Czechoslovakia in 1989, when it first became a democracy. Although Havel had plenty of ideas about what this new country should be like, understanding the dangers of imposing vision, he wisely restrained himself and developed strategic mechanisms that involved the entire country in the process of rebuilding. While he admits that sharing vision did not solve all of the country’s problems, it did create an environment where, “ . . . people believed they were part of a common entity – community” (Senge, 1994, p.298). In this same way, training can be strategically used to create community through the sharing of vision.

Monitoring and Enforcing Ethical Standards

When codes of ethics are aggressively enforced and become an integral part of the company’s culture, ethical behavior in the organization will improve. Enforcement and employee conduct must, however, be measured and evaluated for effectiveness, and altered when necessary. Among the variety of methods that can be used are internal audits, observing employees, surveys, questionnaires, and hotlines. One of the keys to measuring effectiveness is input and feedback from employees (Ferrell et al., 2013).

Another major tool for determining the effectiveness of an ethics program is the ethics audit which identifies and measures an organization’s commitment to its ethical procedures and policies. It uses objective systematic evaluation to determine whether its program and policies are effective. It is not required, but when used demonstrates to stakeholders that the company is committed to improving its strategic planning, and serious about its responsibility to comply with legal and ethical standards (Ferrell et al., 2013).

Organizations of all types play a major role in all of society. As a result of increased competition, advanced technologies, and public scandals, companies are being forced to operate and function at a higher level of ethical standards. Many organizations in their efforts to meet these new requirements will have to re-create and establish a new ethical culture. This major initiative begins with an understanding about the role that organizational culture plays in the decision-making process. Leaders must then be acquainted with new responsibilities connected to new roles as ethical leaders in a new culture. A new ethics programs will have to be developed and implemented with the involvement of employees at every level of the organization. Once implemented, the new ethics program should be monitored and systematically evaluated for effectiveness.

References

Ferrell, O.C., Fraedrich, J., Ferrell, L. (2013). Business ethics ethical decision making and cases (9th edition).

South-Western Cengage Learning. Mason, OH 45040.

Kranacher, M. (2006, October). Creating an Ethical Culture. CPA Journal. p. 80.

Senge, P. (1994). The fifth discipline fieldbook: strategies and tools for building a learning organization.

Doubleday. www.currencybooks.com.

Please follow and like us:

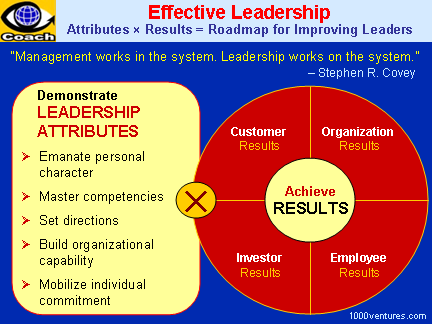

When you approach the arduous task of defining leadership, a new appreciation develops for its complexity. It is a complex phenomenon that can be viewed from many perspectives. For instance, you can talk about the different styles of leadership, such as transformational, charismatic, and transactional leadership, which focus on how the leader leads. There are also different approaches to leadership called leadership theories. An example would be Fiedler’s contingency theory which believed that effective leadership could be best achieved by matching the leader’s style with the organizational situation (Daft, Marcic, 2011). You can look at leadership traits, which are distinguishing personal characteristics of leaders, such as honesty and intelligence.

When you approach the arduous task of defining leadership, a new appreciation develops for its complexity. It is a complex phenomenon that can be viewed from many perspectives. For instance, you can talk about the different styles of leadership, such as transformational, charismatic, and transactional leadership, which focus on how the leader leads. There are also different approaches to leadership called leadership theories. An example would be Fiedler’s contingency theory which believed that effective leadership could be best achieved by matching the leader’s style with the organizational situation (Daft, Marcic, 2011). You can look at leadership traits, which are distinguishing personal characteristics of leaders, such as honesty and intelligence.